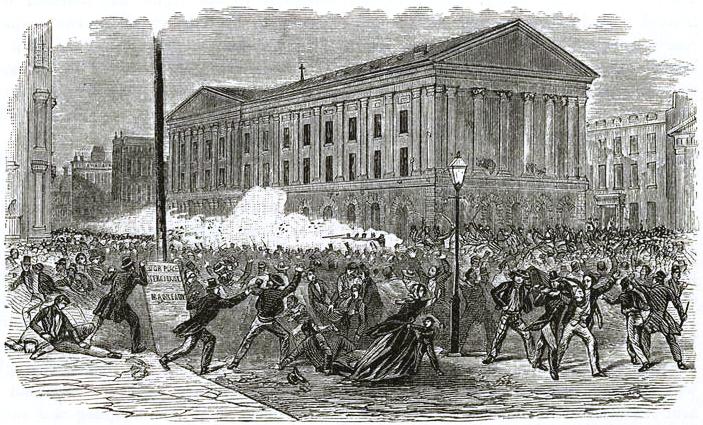

On May 10, 1849, the famed Astor Place Opera House was the site of the worst riot in theater history, and one of the most infamous riots in New York City. The riot was reflective of both class and ethnic tensions in New York City in the nineteenth century. Pre-planned theater riots were not uncommon at the time and were often used to express discontent with a theater policy, a manager or an actor, or even the music used in the performance. However, this riot stood out because of the number of participants and causalities, the amount of destruction, and because it was the last theater riot in the city.

The Astor Place Opera House

The Astor Place Opera House opened on November 22, 1847 at the corner of Astor Place and East Eighth Street.1 The 1,800-seat theater was designed by architect Isaiah Rogers, and society reporter George G. Foster wrote that at the time, “its white and gilt open lattice-work, the richness of the crimson velvet sofas and chairs, the luxurious hangings of the private boxes, and the flood of gas-light shed from the magnificent chandelier and numerous other points about the house, furnish a coup d’oeil of beauty it would be difficult to surpass.”2 Although attendance at the new theater was high at first, the numerous theaters offering Italian opera in the city soon lead to a dwindling number of attendees. The Opera House owners decided to expand their offerings by performing more popular dramas in an attempt to increase attendance.3

William Macready

As part of this new effort, the Opera House booked famous English tragedian William Charles Macready for a four-week run during their 1848–49 season, where he would play the leading role in Macbeth.4 This decision lead the New York Herald to proclaim the Astor Place Opera House the center of the city’s Anglophile aristocracy.5 This was not the first classist accusation leveled at the theater. Some had already accused the theater of attempting to shut out lower class attendees by higher ticket prices and the kid-glove dress code.6

Working Class Tensions

The lower classes in Manhattan, many Irish, viewed the hiring of the Englishman Macready as another assault on the working-class. These residents of the city had long harbored a love for actor Edwin Forrest. A combination of working-class disdain for British culture, stemming from the perceived alienation toward the working-class on the part of British cultural elites, and Forrest's beginnings in the working-class Bowery Theater in New York City contributed to this affinity for Forrest. Many of New York's working-class felt a connection with Forrest. He was the first true American star, and they could claim a connection to where he got his start. Forrest and Macready had a long-standing feud, seemingly stemming from an incident that had occurred when Forrest was performing in London. Newspapers reported that Macready went to see Forrest perform in London and publicly hissed him.7 This alone would probably have been enough to garner Macready a negative reception from Forrest’s fans, but it was exacerbated by the fact that Forrest had also received critical reviews from London newspapers during his time there.8

Adding to this already negative sentiment was the fact that Forrest would also be performing the starring role in Macbeth at the competing Broadway Theater on Macready’s opening night.9 Newspapers, along with the infamous Bowery Boy gang and some Tammany Hall politicians, knowing about the long-standing feud between the two, built on the anti-English sentiment of the city’s Irish working class. They fueled the flames of discontent encouraging the working class to protest against this upper-class, British actor as a representation of all that they hated.

First Performance

On the evening of May 9, Macready’s first performance, the manager of the Opera House gave out more tickets than number of people the theater could hold, building on the popularity of the performance. Once he realized both the number of people coming and that most of the tickets had been taken by people intent on disturbing the theater, he went to the police to request assistance in case a disturbance should occur.10 A crowd assembled outside the theater before it opened, and rushed the doors, filling up all of the seats in the theater.

The first act of the play passed without incident, but when Macready appeared on the stage at the start of the second act, the uproar started.11 Macready attempted to outshout the audience, but people began to throw things at the stage, including rotten eggs, copper pennies, apples, potatoes, and lemons, which splashed the actor’s costume.12 Someone in the audience shouted “Get off the stage you English fool! Three cheers for Ned Forrest!” Someone threw a chair at the stage, Macready fled the stage, and the curtain dropped.13

The Riot

Macready was determined to not let the crowd stop his performance, so he resolved to appear again the next night again, while Forrest would be appearing downtown as Spartacus.14 However, Tammany Hall politicians, who had been instrumental in the rabble rousing during Macready's first performance, harbored a particular animosity for the newly elected Whig government in New York City. These politicians felt that a second uprising by the working-class elements of the city, particularly after Macready had been encouraged by these same men to appear at a second performance, would be an embarrassment to the Whig mayor. An ad in the day’s paper, placed by Tammany Hall politicians, encouraged the mob to show up to that night’s performance, reading:

“Workingmen! Shall Americans or English rule in this city? The crew of the English steamer have threatened all Americans who dare to offer their opinions this night at the English Aristocratic Opera House. Workingmen! Freemen! Stand up to your lawful rights!”15

Tickets were sold only to those known to be friendly to Macready and a police presence of 300 was promised. Although a crowd gathered outside the theater, the police held them back, and the doors were locked once all ticketholders were inside. In anger, the crowd in the street began to throw cobblestones at the theater, breaking several windows.16

Despite the precautions, some Forrest fans were still able to get inside, and yelled to drown out Macready. At one point, they surged for the stage, but the police removed them from the theater. The National Guard Cavalry arrived to try to calm the crowd that remained outside of the theater, but the crowd threw paving stones at the horses and they retreated. The local militia unit, the Seventh Regiment, appeared on the scene around 10:00 p.m, all armed.17 The crowd taunted the soldiers, yelling: “Fire if you dare—take the live of a freeborn American for a bloody British actor!”18 Officers gave the soldiers orders to fire over the heads of the crowd, in an attempt to restore order. However, when this was unsuccessful, they began to fire into the crowd, killing 22 people, and wounding numerous others.19 This finally caused the crowd to disperse, leaving the dead and wounded behind in the street.

Macready was not able to leave the theater until after 1:00 in the morning. He left heavily disguised through the main door, not the stage door. After exiting the theater, he went directly to Boston, where he sailed back to England as soon as possible. He never appeared on the New York stage again.20 Edwin Forrest never publicly commented on the violence.21

The papers nicknamed the theater the “Massacre Opera House” and “Upper Row House of Disaster Place.” Although this was the last instance of theater rioting in New York City, the Opera House never recovered from its association with mob violence, and, eventually, the theater closed and in 1850, the Mercantile Library bought the building at auction for $150,000.22 The building itself was torn down in 1891.23

Very well written. The essay captured my attention and gave great detail and description. I changed some of the passive voice sentences and tried to clarify some other information in the essay. An example is that I noted the 7th Regiment was a New York State Militia unit based in Greenwich Village.

Kate, I added a few links to both Wikipedia articles, which seem to give a thorough context, and to the Folger Shakespeare Library, which had interesting podcasts on the riot from expert academicians. I also included two pictures, the first from the class archive and the second from Wikimedia Commons, who cite the photo as from the NYPL Digital Gallery. They are both in the Public Domain.

I agree that this is a very compelling and well-written piece. The style edits I made were minor, mostly consisting of shortening sentences and eliminating so many commas.

Thanks everyone for all of your help! I thought that the Folger Shakespeare Library links, in particular, gave very good context to what was discussed in the essay. There were a lot of theater-specific underlying issues that I didn't get into in the essay, and I think that directing people to Folger was awesome for those who would want to explore more. I thought the images added a lot, and I really appreciated everyone who helped make the writing tighter.